|

The McGuire Rig

by Donald J. Taylor

Recon Team Leader

July 1968 July 1970

|

Project

Deltas mission during the Vietnam War was long range reconnaissance, and

as such, it depended on U.S. Army UH-1D/H helicopters, primarily from the

281st Assault Helicopter Company, to insert and extract its

long range reconnaissance teams.

When a reconnaissance team became

compromised and could not break contact with the enemy, the team would

usually request an emergency extraction, and an emergency extraction, more

often than not, was accomplished using the McGuire rig.

The McGuire rig was the method used to extract a team by rope when the

extraction helicopter could not descend low enough to either sit down, low

hover, or utilize its two 35 ladders. If the helicopter could descend

down to at least 100 feet altitude above the team, McGuire rigs were

dropped to the team and they were extracted by rope.

A McGuire rig was simply a 15 x 3 nylon strap (type A7A) fashioned into

a loop large enough for a man to sit in and with a smaller wrist loop sewn

into the A7A strap to prevent the wounded or unconscious from falling out.

The top of the A7A strap was tied to the outside (running) end of a 120

foot inch nylon rope and stowed on the left side of the helicopter

inside a Griswold container (a thick canvas weapons container). |

Three Project Delta soldiers ride a McGuire rig during training at Mai

Loc, I Corps, 1969

|

|

The nylon rope was S folded and secured by rubber bands to two canvas

strips that had been sewn into the inside of the Griswold container. The

Griswold container performed three functions: to keep the rope from

fouling, to protect the rope when walked on, and to protect the rope

from the sharp outer edge of the helicopter floor.

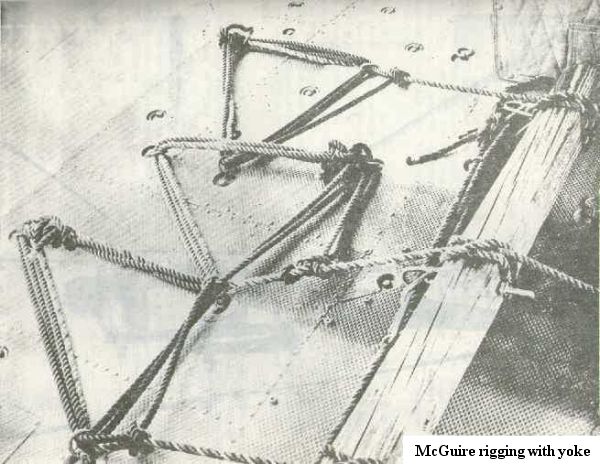

Floor of helicopter with teak wood yoke at right, ropes running

through rings in triangular fashion at left.

The inside (standing) end of the rope was clove hitched to an 6x 6x 5

teak wood yoke in the center of the helicopter floor and secured by snap

link to at least three anchor rings in the floor of the helicopter. The

yoke had three large O rings bolted into its side and was snap linked

by these O rings to floor anchor rings on the right side of the

helicopter. A sandbag weighing about 20 to 30 pounds was tied to the

bottom of the A7A strap loop and tucked up under the outside end of the

Griswold container. Three McGuire rigs were usually installed in each

helicopter.

The heart and soul of the McGuire rig system were its ropes, and good

rope maintenance was crucial to the dependability of McGuire rigs. The

inch nylon ropes were rated at 3600 pounds. After each use, ropes were

carefully inspected, and if even one thread in a rope had been damaged,

it was discarded. Each thread ran the entire length of the rope and if

even one thread was damaged, the entire rope was weakened.

|

|

A rigged

helicopter can be seen behind Bill Dill. All that is visible is the

ladder, a Griswold container, and a sandbag. |

In the life of these 120-foot ropes, there was a 20% stretch factor

before they were no longer safe to use. Each time a rope was used, it was

stretched a little bit longer until it had lost all of its elasticity at

about 140 feet, and before this happened, it was replaced. But this

created a problem with varying lengths of rope. If a new 120-foot rope was

used to replace a damaged rope, it would be shorter than the other two

McGuire rig ropes and its rider would ride possibly 10-feet higher than

the other two riders. To correct this, the new rope was tied between the

bumpers of two vehicles and the rope was stretched until its length

matched the other two.

After the McGuire rigs had been installed in the floor of the helicopter,

an 80-foot aluminum and steel cable ladder was installed on top of them,

with 35 feet of the ladder rolled up and secured between the skid and the

troop deck on each side of the helicopter. The center of the ladder was

snap linked to anchor rings in the helicopters floor, and the ladder

rolls were attached to floor anchor rings with standard air- |

|

craft seatbelts. To release the ladders, the seatbelt releases were

kicked open, and of course, the order to release the ladders was Kick

the Ladders. After the ladders had been lowered, they could be pulled

back up to the helicopter by a rope that ran the entire length of the

ladder.

When the decision was made to employ the McGuire rigs, the rolled up

ladder on the left side of the helicopter was pulled inside and stowed on

the right side. To protect the ropes from the sharp outer edge of the

helicopter floor, the Recovery NCO would unfold the Griswold containers

and slide the outer end of the containers over this area, making sure that

the thick canvas fabric of the container was between the ropes and the

floor edge.

As soon as the helicopter had descended to less than 100 feet above the

Recon team, the Recovery NCO would pick up each sandbag and toss them out

and over the skid. The weight of the sandbag pulled the McGuire rig and

rope out of the Griswold container and down to the ground below at a high

rate of speed. It was up to the Recon team to dodge the sandbags.

SFC Norman Doney supervises SSG James Coalson and SFC Paul

"Mickey" Spillane in the installation of an extraction ladder on a Huey at

Phu Bai, 1968. Doney scrounged the ladders from CH-47's and equipped 281st

AHC helicopters with them to extract recon teams. Doney later did the same

at CCC.

The standard composition of a Project Delta Recon team was two U.S.

Special Forces and four Vietnamese Special Forces, and it took two

helicopters to extract the team by McGuire rig. The Recon SOP for McGuire

rig extraction established that the first helicopter would lift out three

Vietnamese and the second helicopter would lift out the two Americans and

one Vietnamese. Because they had the radios, the Americans were always the

last to be extracted.

The SOP also stated that each man would snap link his CAR-15/M16 by the

carrying handle to his LBE on his right side with the muzzle pointing

forward. This arrangement allowed the team to have one-handed use of their

weapons during exfil and could return fire if necessary.

The moment the sandbags impacted on the LZ, the first three men would run

out, grab the McGuire rigs, snap link their rucksacks into the bottom of

the A7A strap loop, slip their left wrists into the wrist loop, step into

the loop, look up and signal with a thumbs up to the Recovery NCO that

they were ready for lift off. When the Recovery NCO saw that all three

were ready, he would direct the pilot to lift off. As the helicopter rose,

the ropes tightened and each man could then sit in the A7A strap loop of

their McGuire rig. They would link arms and legs as they lifted off the

ground and become one solid mass plowing through the air a hundred feet

below the helicopter. The linking of arms and legs was done in case a rope

was shot in two, as a man might be saved by his team mates hanging on to

him.

281st AHC Slick - Rigged and Ready

If a relatively safe clearing could be found enroute back to Project

Deltas Forward Operating Base (FOB), and if the helicopter had the fuel

to spare, the helicopter would sit down so the team could board the

helicopter. If not, then the team was in for a long and uncomfortable

ride, as sitting on that three inch nylon strap for any length of time

could become quite painful.

It was not uncommon for a McGuire rig ride to last an hour or more, as

most Project Delta Reconnaissance Areas of Operation (AO) were at the

maximum range of the UH-1D/H helicopter. Even with a full load of fuel,

helicopters would frequently leave the FOB with barely enough fuel on

board to reach the AO, spend no more than fifteen minutes on station, and

then return to the FOB. If the extraction helicopter used more than its

allotted fifteen minutes while recovering the team, the pilot wouldnt

have enough fuel left on board to divert to an LZ, sit down, and take the

team on board. When this happened, the team would have to ride the entire

one-hour (+-) return flight to the FOB in the McGuire rigs, and they would

frequently just barely make it back to the FOB before the helicopter ran

out of fuel.

The Recovery NCO had a machete on board the helicopter, and he was to cut

the McGuire rig ropes if the team became tangled in the trees on lift off.

If the helicopter developed mechanical problems and began to fall, he was

to wait until the team was at tree top level before he cut them loose. All

agreed that the team had a much better chance of surviving the impact with

the trees or ground than they did of surviving if the helicopter crashed

on top of them.

McGuire rigs were so painfully uncomfortable that when SOG developed

the STABO rig in 1969, Delta Recon requested that Project Delta also adopt

the system, but the request was refused. For logistical reasons, it was

determined that the STABO system was not practical for a unit the size of

Project Delta. For Project Delta to retain the capability of providing

emergency extraction for everyone in the unit, not just Recon, but every

Road Runner, BDA Nung, and Ranger would have had to have a STABO rig. If

the Project had adopted the STABO system, the unit would have had to

procure and maintain several hundred STABO rigs. With the McGuire rig,

Project Delta only had to maintain no more than 20 or 30 rigs at any one

time, and could quickly make more if needed.

|

|

Project Delta's Sergeant Major Charles T. McGuire -

renown for the McGuire rig used to extract recon teams. |

The STABO rig was a machine stitched harness similar to a parachute

harness and was quite expensive and time consuming to manufacture. The

harness was made of similar nylon material as the A7A strap, and was worn

in the field as load bearing equipment (LBE) until it was needed for a

rope extraction. STABO harnesses were made in small, medium, and large

sizes.

To ready a STABO harness for rope extraction, two leg straps were brought

from the back of the harness up between the legs and snapped into D rings

mounted in the front of the harness. A standard issue pistol belt laced

through the center of the rig was buckled tightly around the waist of the

wearer, a chest strap was fastened across the chest, and two snaps at the

top of the harness would snap into two D rings attached to the rope

dropped from the helicopter.

When the STABO and McGuire rigs were compared, the only thing the STABO

rig had over the McGuire rig was comfort during the ride. For

practicality, the McGuire rig couldnt be beat: |

|

The McGuire rig remained in the helicopter and was not carried in the

field, as was the STABO rig. The STABO harness, when worn in the field as

LBE, was not only heavier than LBE, but it did not fit well under a heavy

rucksack, nor did it properly distribute the weight of ammunition,

grenades, and canteens and could become rather uncomfortable after it was

worn a few days.

The McGuire rig was always there when needed. With the McGuire rig, a

soldier could become separated from his gear and still be extracted by

rope. However, with the STABO rig, if it was lost it in the field, the

soldier could not be extracted unless he could find a sit down or ladder

LZ. There was at least one American in CCN who is still out there because

he became separated from his STABO rig.

And last but not least, how would the Road Runners have worn a STABO rig

with an NVA uniform?

Project Delta retained the McGuire rig until the end. They may have been

uncomfortable, but they were cheap, reliable, and effective. A debt of

gratitude is owed Sergeant Major Charles T. McGuire for creating a piece

of equipment that was just what was needed at just the right time. An

untold number of American and Vietnamese Special Forces soldiers lived to

fight another day simply because of Sergeant Major McGuires innovative

and timely creation.

Sergeant Major McGuire is alive and well and living in retirement out on

the coast of North Carolina. But not for the U.S. Armys mandatory

retirement policy, he would still be on active duty and leading another

generation of Special Forces soldiers in combat.

|

HOME

|